Note: Where they are available, full resolution photographs can be accessed by clicking on the image.

Related Pages: System Documentation.

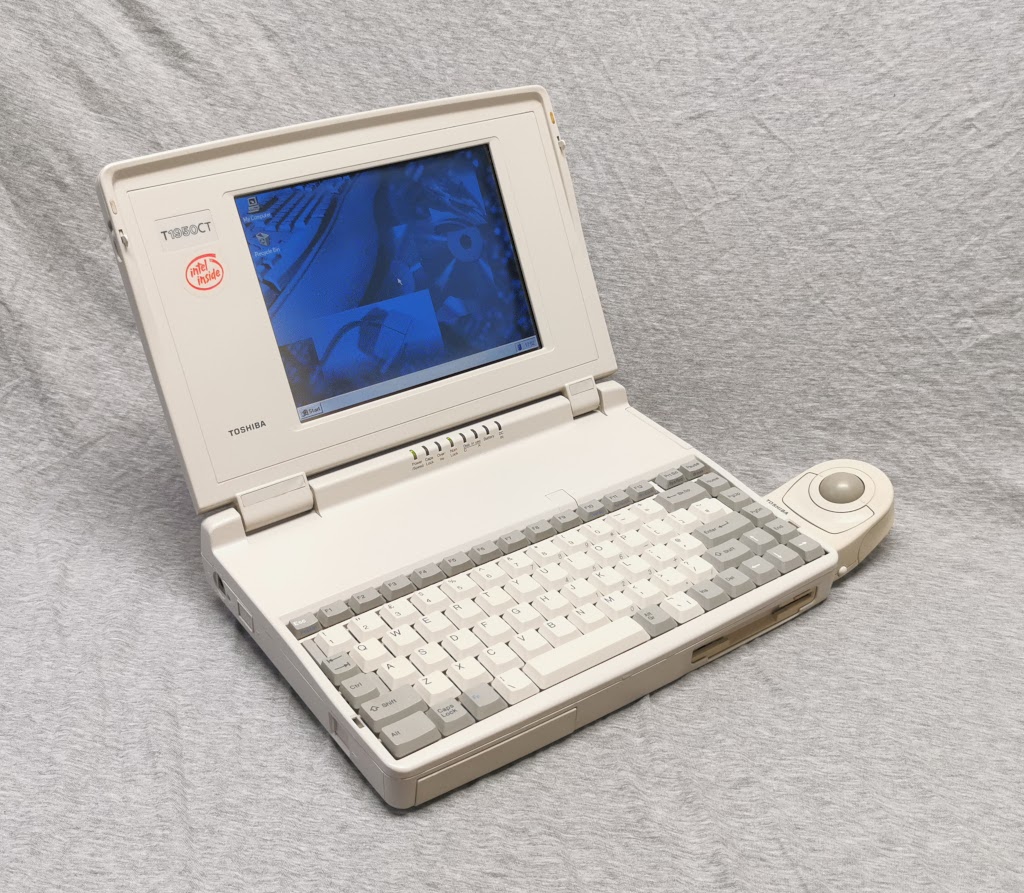

Toshiba T1950CT System Specification:

Manufacturer: Toshiba.

Model: T1950CT (Internal model code PA1153E)

Launch Date: Not known exactly - estimating late 1993 to early 1994.

Production Date of this machine: Mid 1994.

CPU: Intel 80486DX2 at 40MHz.

Memory: 4Mb internal, expandable to 20Mb via proprietary DRAM card.

Display: 8.5" Active Matrix TFT. 640*480 native resolution at 256 colours. System can support up to 1024*768 available using an external monitor.

Storage:

320Mb 2.5" IDE Hard disk.

High density 3.5" Floppy disk drive.

Power Requirements: 18V DC at 1.7A maximum. Barrel jack with centre positive.

Battery: Single removable NiMH 12V 2400mAh pack. Expected battery life of 2-3 hours. Inbuilt rechargeable batteries for RTC/CMOS

Weight: 3.2Kg.

Throughout the closing years of the 1980s and the early days of the 1990s if you were in any way interested in portable computing you could most likely pick out offerings from most of the major players from quite some distance away. This was because at that time most of the companies involved still had very much their own ideas about what was the best approach to making a portable computer. By the mid 1990s these had pretty much all coalesced into something which even today you could immediately recognise as a laptop computer. Simply because as it turns out, that's a shape and layout that just works. This is probably why I have little interest in portables made after that date, as for the most part they're all very similar aside from the occasional one here or there which stands out for some reason in particular.

During the early days of portable computing Toshiba had always been one of the big players. I've always had rather a soft spot for their portable machines. The T1950CT shown on this page which dates from early 1994 being for me a machine which nicely bookends the "early laptop" era for them I think, having started in 1987 with the T1000 shown below in both closed and open configuration.

This example has yellowed quite a bit, it originally would have been far closer to the light cream colour as the main machine shown on this page (which has somehow survived without any real yellowing noticeable aside from the floppy drive face plate).

Quite a lot of people consider the T1000 to be the first example of a "modern" laptop computer in that it was a fully portable, self-contained machine which could be used for most general purpose computing tasks of the time. Whether that accolade goes to the T1000 or the T1100 (which despite the higher model number actually debuted a couple of years earlier just to confuse matters) is always up for debate, but personally I would give it to the T1000 as it's a far more compact, travel friendly design and having MS-DOS burned into ROM makes it far more user friendly on the move as it saves continual disk swapping. To my mind the T1100 is more the genesis of the portable desktop replacements such as the T3100, T3200 and T5200.

Having examples of the T1000, T1200 (a personal favourite), T1600, T1850C and this T1950CT in the collection is quite interesting as you can very clearly see year-by-year how the design has been progressively refined.

This particular machine wasn't one that I was actively looking for - in fact I've very much deliberately NOT been looking for any more computers lately as I already have far too many machines and nowhere near enough house in which to properly store them all. However a friend spotted this on Facebook Marketplace and pointed me at it. As the price was very much right and this looked to be a pretty tidy example complete with a couple of peripherals and all the cables I wasn't about to say no.

Given there is only a year between the T1850C I was expecting the specifications to be pretty similar - and given the fairly conservative 80386/25MHz headline for the T1850C I was quite surprised to find this is running a 40MHz 80486 DX2. A Decently powerful processor for a portable machine in 1994. The performance difference would actually be even bigger than the near doubled clock speed might suggest in the right applications, given that the 486DX chip has the advantage of an onboard L1 cache AND an integrated math co-processor.

In addition to the sheer additional computing grunt available, the user would never be able to miss how huge an upgrade the "T" suffix on the model number provides. That indicates that this machine is fitted with an active matrix TFT display rather than the passive matrix DSTN display panel as were pretty much standard at the time. The T1950 was actually available in three variants - just the basic T1950 which used a monochrome edge lit TN panel, the T1950CS used a DSTN colour display, and the top of the line T1950CT here had the TFT panel.

If you're not familiar with early colour LCD displays, you may not have come across a DSTN display before as they largely vanished by the late 1990s. They're immediately recognisable though by having very, very narrow viewing angles, typically extremely poor contrast and response times that can pretty much be measured in seconds. They were a passable solution when using DOS applications (though I reckon really weren't worth the extra power draw and cost over a halfway decent monochrome display in most applications I reckon), but particularly the horrifically slow response times made them a real chore to live with as soon as graphical environments like Windows became commonplace. I have an IBM ThinkPad 755Cs which has a DSTN panel, and pretty much any time you make the mistake of actually moving the mouse pointer you then have to spend the next five seconds trying to figure out where it's actually got to as it basically just disappears until half a second or so after you've stopped moving it. You may remember a (usually annoying!) option to enable "pointer trails" in Windows 3.1 and 95 (can't recall if it survived later than that) - that basically exists to help anyone using a DSTN screen keep track of the cursor! There's your useless bit of information for the day.

Enough waffling about display technology, let's actually take a look at this machine shall we?

I give you...one highly unassuming, slightly off-white plastic rectangle.

Not much to see on the front of the machine, just the battery pack on the left, floppy drive on the right.

The floppy drive face plate is the only part of this machine which has yellowed really noticeably.

Close ups of the Toshiba and model badges on the lid.

Moving around to the right hand side of the machine things are a little busier, though unlike on most modern machines everything by default is safely hidden away behind covers. Which somewhat miraculously on this machine are all still present and correct.

The large slot nearest the front of the machine is for a trackball (or BallPoint Mouse as they called it) which clips onto the side of the laptop. More on that later. The next set of ports are for a standard PS/2 compliant mouse and keyboard to attach. Due to how it interfaces with the machine it's not possible to use these ports AND the trackball at the same time - to prevent users trying, the cover blocks off either the PS/2 or DCBM (trackball) ports making it physically impossible to plug both in together.

DCBM (trackball) port open, and PS/2 ports shown blocked off.

Then below with the DCBM port closed, which opens up access to the PS/2 ports.

It's a very simple bit of engineering just using a single sliding bit of plastic. However it's quite a clever design as it's a pretty foolproof way to prevent users plugging in both things at once and then at best wondering why something doesn't work, or worse actually damage something. At the very least it was likely in period have caused enough head scratching as to cause the user to refer to the manual - or just accept you couldn't use both at once without having a clue why it was set up like that.

The trackball itself is an interesting design, and is one I actually came across an example of many years (or possibly decades!) ago.

I had no idea what it was actually meant to be used with as I'd never seen the bizarre looking connector before (which I now know is referred to as a DCBM connector), nor indeed have I seen anything equipped to connect to it since.

Interesting to see that it's actually badged as a Microsoft product, though clearly Toshiba made. I'm assuming that this is largely down to there still being a few competing standards in the mouse world at the time, and they wanted to be sure that they had one which was fully compatible so went all out to actually get a licence in place.

I suspect the original one I discovered long ago is most likely still buried in a box in the loft somewhere.

This clips directly onto the side of the machine like so.

It can then be adjusted to tilt up to about 45 degrees to suit the user.

The button nearest the camera is mirrored on the opposite side of the device. Only the far one appears to register (at least with this driver configuration), as what would conventionally be the left mouse button. The one nearest the trackball itself registers as the right mouse button. After a little bit of experimentation I have personally found this to be the most comfortable way to use it.

By the standards of pointing devices on portable machines in the early 90s, I'll give this one a solid "okay" rating I think. Touch pads were still a few years away for mainstream machines, and I personally find this to be far more pleasant to use than the track point nubbin that IBM came up with as their solution. Even though this one needs a good clean it still works well enough to not be actively annoying and is reasonably comfortable. Especially remembering that computer use in the early 90s was by and large far less mouse heavy than it is today.

Moving on from the trackball, towards the rear of the right hand side of the machine there are two vertically stacked hinged flaps. The top of these covers a slot in which a DRAM expansion card can be installed (up to a maximum of 16Mb). This system has been equipped with a 4Mb card - taking the system up to 8Mb with the 4Mb built in.

Here's a closer look at the memory expansion card itself.

I probably don't want to know what that little 4Mb card originally cost. There's nothing particularly special about it from a technological standpoint, it's just a little PCB containing normal DRAM chips enclosed in a slimline case with a connector on one end. A few manufacturers of laptops provided facility for installation of memory expansions this way as it removed the requirement to physically open the case to install it, making it far more feasible for the end user to install themselves. While the cards are the same size and shape as a PCMCIA card, the connector is different (the memory card has offset pins), so it's not possible to mistakenly plug a PCMCIA card into this slot or vice-versa.

Below that slot there's a larger door which conceals a single PCMCIA 2.0 card slot, in the case of this machine came equipped with a modem as would have been quite common to see on a portable machine back in the day.

Interestingly there's a little smaller fold down flap in that door to allow for a cable to connect to the card. Really handy if you're using a card in there such as a Modem, network card or SCSI adapter which would require a cable to be plugged in.

On the rear of the machine the theme of keeping things protected by covers continues.

With the covers slid open the usual selection of ports you would expect on an early 90s machine are present. A 15-pin VGA connector, parallel port and 9-pin RS-232 serial port. At the far right there is an attachment point for a security tether. This is the earliest machine I can personally recall seeing that feature on.

The left hand side of the machine has a handful of items on as well.

From the rear we have the DC input jack (18V DC centre positive, 1.7A max), a recessed system reset switch, the power button, and nearer the front of the machine, the battery release catch. That catch took me a second to figure out how to use initially - you need to slide the cover aside (which has a stiff enough spring on to make it feel like you're actually working the latch in doing that), but then you *also* need to press the latch which sliding the cover aside reveals to actually release the battery. Not something you're ever doing to do accidentally.

As you would expect the underside of the machine doesn't really have much to show. The bottom of the battery casing, a model label, a release lever for the PCMCIA card, and four feet.

The rear feet do actually extend by about 10mm to help keep the keyboard at a more ergonomically friendly angle if you pull the little latches next to them.

This feels a good deal more sturdy than the fold-out arrangement on my IBM ThinkPad 755Cs, but even so I'm sure a good number of these got broken back in the day.

This shows how it elevates the rear of the machine. It's not a huge lift, but does make typing more comfortable.

Really obvious from this angle how much more the profile matches that of a modern laptop than most others on this site.

Opening up the lid reveals a fairly conventional looking machine. While the display looks tiny by today's standards at only 8.5", this was pretty much par for the course on portables of the time. Also keep in mind that the display resolution is only 640*480 and that software of the time was generally designed with this in mind it's entirely usable.

Very conspicuous immediately to the left of the display is a bright red "intel inside" sticker.

Which I actually found a little surprising as it seemed a little bit of an anachronism. As I understand it, Toshiba had pretty much exclusively used Intel CPUs since they left behind the 286 architecture in the dying days of the 80s. The latest machine I've seen with a non-Intel CPU was a 1989 made T1600 which uses a Harris made 286.

The Intel Inside logo of course became a very common sight in the mid to late 90s as pretty much as soon as the Pentium hit the ground AMD and Cyrix (and probably many others I've never heard of or have forgotten) were leaning heavily on the market with their own alternatives. It just feels a little odd to see it on a machine from this particular moment in time though, as my reaction there is basically "Yeah...well what else would be inside?" The only non-Intel 486 CPUs I actually own are from right at the end of its run in the form of a couple of AMD made 100MHz DX4s. I will say though, Windows 3.11 absolutely flies running on that hardware - especially if you've got enough memory to buffer the entire OS and your most commonly used programs into RAM on startup...

Back to the machine at hand - the keyboard layout is standard Toshiba fare for the time period, barely changed from the T1200 save for a few tweaks to accommodate the function keys running to F12 rather than F10 on the T1200.

Note the position of the caps lock button. While this is something that I personally find makes far more sense (I use control all the time - the only times I can think of caps lock ever being used unless I'm entering code that needs to be in caps is by accident), this must be one of the latest mainstream machines I can think of which still has control in its rightful place by the A key.

Obviously this is a British keyboard layout, so a couple of keys will probably be slightly different if you're from areas using a different keyboard layout.

Sadly in the interests of reducing the depth of the machine, this has lost the lovely Alps mechanical keyboard that most of the 80s laptops plus the big mains powered luggables used. This is a membrane board with a rubber dome assisted plastic spring.

Here's what's under the key caps.

Then removed to show the individual components.

While it's a shame to lose the Alps keyboards of the older machines as they

were truly lovely to type on (and this is one of the reasons that my T1200 still

gets used regularly for writing), though with portability being an ever bigger

driver I can absolutely understand why Toshiba decided to do this. It does

reduce the overall profile of the keyboard by a good 50% compared to the earlier

ones - and I'd imagine more than halves the weight.

As far as typing action goes - it's thoroughly inoffensive. Very smooth, and

extremely quiet...Which I guess does work in its favour compared to the Alps

boards which *are* somewhat on the noisy side if you're sharing the space with

colleagues or using a machine in a public area of a hotel or similar.

While it's not going to win any favours for the tactile experience or help your

typing speed to push over its normal average, it's absolutely fine and still

better than the keyboard on plenty of modern laptops to be absolutely honest.

Above the keyboard between the screen hinges sits a rank of eight status LEDs.

I was slightly nervous as to what condition this machine was going to be in when it first turned up as it hadn't been especially well packaged by the seller. Nevertheless it survived the trip unscathed, not least I reckon due to having been in the middle pocket of this absolute brute of a Targus branded case.

In the case were a few accessories as well as the computer itself. The tendency for them to be stored in cases along with all their "stuff" is a nice feature of portables as it means that things which in the case of a desktop system would often be lost to the mists of time remain together.

The original - albeit rather filthy - power supply.

Here are the model details if you happen to be looking for one of these or a compatible unit.

The interface leads to go with the PCMCIA modem card. This is always nice to have as pretty much every brand used a different proprietary connector at the card end.

The final item in the case (aside from a couple of blank 1.44Mb floppy disks anyway) is a little bit more rare to find still with the machine I think, in the form of a 12V charging adapter.

Worth noting that 20W at 18V is only 1.11A - so wouldn't actually meet the specified maximum power draw to both charge and run the computer at the same time. According to the specifications the maximum power consumption for this machine is 30.6W.

Being quite familiar with the capacitor issues which plague the earlier machines I was somewhat torn over whether to power this one up or not.

On that note, if you have come across a Toshiba T1000, T1200, T1600, T3100SX or T3200, PLEASE DO NOT plug it in until it has at the very least been inspected to check for capacitor leakage. The consequences of just plugging it in - even for just a second - particularly on the T1200 and T1600 machines can be catastrophic damage to the power supply PCB and motherboard in the machine. This probably applies to other models as well, but these are the ones I'm specifically aware of suffering from these issues. On the T1200 this is a particular problem as one of the tracks on the PCB which most commonly suffers corrosion damage is a feedback line, resulting in the power supply board sending full, unregulated 12V into parts of the machine which are only meant to see 3.3V or 5V before the power supply itself eventually goes "pop."

I decided to risk it in this case.

Couple of reasons behind this: The first being that the seller had clearly stated that they had already plugged it in and that a green light had come on. So if anything was going to blow up it probably already had. Secondly was that there is a particular smell to the electrolyte which leaks from the capacitors used in these machines (or possibly the corrosion it causes?), it's just something you come to recognise when you've been involved in this hobby for this long, and this machine was completely devoid of "the odour." It should be noted that this is a very different smell to the almost sweet smell emitted by semiconductors when the magic smoke has escaped - though the two DO very often go hand in hand if someone has tried to power the machine up before, especially if it's a T1200 or T1600. See my message in red in the previous paragraph...

Before I plugged it in though I did a little bit of checking. Firstly was whether the power supply was outputting a reasonable voltage, which it was albeit slightly on the low side. Secondly was to take a closer look at the battery to see if there were any signs of it leaking, bulging or generally showing signs of distress.

No external signs of problems, though I don't actually expect it to be any good obviously! Even if the February 1998 date written on it was a replacement date (which given there's what looks like a 1997 date code present would make sense), it's still a good 20 years beyond its expected useful life by now.

Initial power up was entirely lacking in drama. With the supply hooked up the green DC In LED lit up, followed after a couple of minutes by an amber battery status LED appearing suggesting that it was at least attempting to charge.

Actually attempting to power the machine up resulted in it immediately tripping out, though this wasn't entirely unexpected. I've found a few of these require there to be at least some juice in the battery for them to properly power up. Even with a more substantial power supply than it originally shipped with and a fully re-capped power supply board, my T1200 is really touchy about starting up with either no battery or a stone flat one fitted.

Waiting a few minutes before repeating this experiment resulted in the machine making it slightly further through power up, this time attempting to spin up the hard drive before it fell over. So I figured I would leave it to its own devices to see if the battery would take a charge for a while. Leaving it to itself in this case actually meant "watch it like a hawk while tidying the kitchen around it."

It seemed to get very slightly further after being left for half an hour or so but still died. On a hunch I tried something - powered it up initially just on the battery - which indeed got the drive up and spinning, then plugged the DC input back in. I think the power supply itself is struggling. It's worth noting that since allowing the internal batteries (both the CMOS/RTC and suspend-to-RAM ones) that start up when plugged in has been absolutely 100% reliable.

While it was a little bit of a hack, it gave us very clear life from the system and once the screen lit up proved that it had indeed survived the trip intact. After a few seconds we got the correct system beep and a selection of error messages I had fully expected to see on screen.

This is the standard complaint to expect from one of these machines if the RTC/CMOS battery is flat and the BIOS values have been lost.

Duly pressing F1 dropped us into the standard Toshiba BIOS setup screen - which is really very basic by today's standards. It did however provide us with some useful information. Apologies for the horrible photograph by the way, I was sitting at the dining table when doing this initial testing with the sun basically right behind the display so major reflection issues were pretty unavoidable.

Things we were most interested in seeing there were the memory size being correctly reported as 8Mb, and the hard disk being detected, showing here as the larger capacity (200Mb and 320Mb options were available). Of course this didn't give us any indication of whether it would actually read/write successfully or if there was indeed even any data on there much less a bootable operating system.

Somewhat to my surprise restarting the system from the above setup screen after a few seconds popped up this boot screen.

This machine would originally have shipped with Windows 3.1, so it's obviously been upgraded at some point in its life.

After a surprisingly short boot process we were dropped into a seemingly fully working Windows 95 desktop.

The System Properties screen showed the basic configuration to be pretty much as I had expected.

The "Registered to: Toshiba Customer..." makes me wonder if this was indeed an upgrade install over the top of the original Windows 3.1 installation.

A quick nose around the system revealed absolutely nothing by way of personal data, and aside from Lotus Ami Pro having been installed, a pretty much vanilla Windows 95 install. The system also seemed to be perfectly responsive and stable so at this point I'm not particularly inclined to do my usual wipe and start afresh approach here. Though I did feel the need to tidy up the desktop a bit.

I also did a bit of general housekeeping like making sure the hard disk was given a thorough test including a surface scan which it passed with no issues. I think it might have been a little overdue...

While seeing such a large number here is somewhat amusing it's also quite useful. A little math shows this to be 24 and a quarter years (less a couple of weeks), so shows that this system was most likely in use in 1999, being put away and forgotten about at only five years old. Not really massively surprising though when you keep in mind how fast the world of IT was changing in the late 1990s, especially where portable computers were concerned. I picked up a second hand Pentium class laptop towards the end of 1998 for relatively little money (we were pretty hard up so weren't in a position to spend money on anything fancy) for my school work - so for the average user this little Toshiba would by 1999 been a very bulky, heavy and underpowered boat anchor. Bit of a contrast to today, when I'm still using a mid-range laptop I bought in 2009 quite happily in 2023 - all it's needed along the way to keep it entirely usable has been some extra memory, a fresh battery and the mechanical hard drive replacing with an SSD when the prices came down to a point where there was just no reason not to. While I'm never going to run the latest games on it - despite being 14 years old it's entirely usable on a day to day basis for normal productivity tasks. Technological progress this side of the millennium really has been far more incremental than revolutionary in the conventional laptop field, that battlefield really having moved to the handheld market.

Helpfully the hard drive test came through just fine, including the surface scan. I'll make a point of doing rather a more strenuous test of this drive before I really trust it for anything vaguely important, but generally I've found that if drives of this sort of era are going to cause trouble they generally do it pretty quickly after being resurrected.

Not really any software on here aside from Windows other than Lotus Ami Pro.

This isn't a particularly exciting piece of software, essentially what by the mid 90s was a pretty run-of-the-mill WYSIWYG Windows based word processor. Though Ami did actually beat Word to the marked originally by around a year. Version 3.1 I believe was the last to use the Ami Pro branding, before being rebranded as Lotus Word Pro in 1996.

Another very conspicuous menu there (echoed by several default icons on the desktop) is the Online Services entry.

This was somewhat symptomatic of the degree to which Microsoft were very much shoving the internet down your throat at this point in time. Having realised that in the early 90s that they had fallen hopelessly behind in taking seriously the potential of the small but steadily growing phenomenon that was the World Wide Web, they went all out in efforts to reverse that as of Release B of Windows 95, including Internet Explorer and facilities to connect to several popular internet service providers out of the box. A decision which landed them in no small amount of hot water legally as providers of competing web browsers (many of which were commercial, paid software at this time) accused them of abuse of their market position by shipping IE with their own OS. Eventually after a biblical amount of legal wrangling the courts agrees and Microsoft were forced to pay a pretty substantial fine. That didn't change the fact that their bundling of IE with the OS had already caused irreversible changes to the market - and essentially had already all but killed off Netscape Navigator which was until the mid 90s, the biggest name in web browsing. It's somewhat interesting to see 20+ years later that the tables have very much turned, with Firefox (which is the modern-day descendent of Netscape Navigator) and Google Chrome being the leaders in the field, with Microsoft's Edge browser limping along in the background - and even then in my experience more often than not only actually being seen in the real world on corporate machines where there's no facility allowed for the installation of third party applications!

A bit of poking around did reveal one part of the machine which wasn't working - and that was the floppy drive. One of the concessions that Toshiba made to get the drive height down was to use a belt drive between the motor and the disk spindle on these drives, and these have usually by this point in their lives started to perish or have snapped entirely. This one had done the latter. This initially hampered my ability to get any software onto or off of the machine as I couldn't immediately think of anything I had to hand which would work just out of the box. I've got a couple of PCMCIA SCSI or network cards and a parallel port Zip drive - however both of these would require the installation of drivers before they would work - drivers which I had no way to get onto the machine. Hypothetically I could have hooked up via the serial port to another PC via a null modem cable and got the files sent over via Telnet - however I did enough messing around with nonsense like that back actually IN the 90s, and I gained enough grey hairs at the time trying to make it cooperate even when the knowledge was fresh in my mind. If I got that desperate I would remove the hard drive, copy whatever I needed onto it via another machine and then just reinstall it. A friend however presented me with a far more elegant solution to my problem in the form of a passive PCMCIA to CompactFlash card adapter. Well - it's actually an IBM MicroDrive one in this case, but the two are interchangeable.

This allowed me to copy over CheckIT, which is my usual go-to piece of software for investigating what's under the hood of a new machine.

No particular surprises there. Though it was nice to finally have a proper confirmation of what the processor was clocked at as I had seen conflicting reports on Google results as to whether it was a 40 or 50MHz chip - 40 it turns out is the correct answer.

What followed next was some disassembly. A couple of reasons for this. Firstly was that I wanted to ascertain how much of a pain it was going to be to get in to the floppy drive to replace the drive belt (it turns out the answer was "a lot" as it's pretty much the last component to be released from the case). Secondly I wanted to examine the power supply to look for any signs of capacitor leakage. Thirdly I wanted to properly clean the keyboard.

While this machine was several of orders of magnitude cleaner than most are when they arrive into my care, the keyboard was still rather gross, especially visible once the key caps were all removed.

I really would have liked to remove this plastic panel to give it a proper wet scrubbing, sadly it's very securely bonded to the PCB behind it so that's not happening. I was able to get things looking far better though.

While the keycaps were sent through the wash I continued pulling the machine apart. In we go...

It pretty quickly becomes apparent when dismantling a machine of this era exactly where the areas limiting how compact they could make a laptop were - and that basically means storage and battery. The actual "computer" and power supply is entirely contained within that silver portion towards the top of the frame nearest the base of the monitor. Everything this side of that is the battery (lowest), the hard drive (centre) and floppy drive (top). This is what the motherboard looks like when removed.

Forgive the horrible reflections - I had the workstation lighting set up for intricate work dismantling a computer rather than photography here!

From left to right the significant components I can easily identify are: the PC speaker (round silver thing to the far left, the display controller, WDC labelled IC - first time I can recall seeing a Western Digital display controller, they're more commonly associated with hard drives, the system status LEDs along the centre of the top edge of the PCB, and the main processor roughly two thirds of the way across. The brown socket is where the memory expansion module plugs in.

The underside mainly seems to contain the video memory (two chips about a third of the way from the left), a single large ASIC towards the centre of the board which is performing the functions of what would normally be several "housekeeping" chips on a conventional 486 PC motherboard and the on board system memory over to the right. The black slot connectors hook up to the power supply and interface for the expansion ports/hard drive which sit below the motherboard. Not much to it compared to those which had come before it.

I didn't find any evidence of existing capacitor leakage in the power supply, however will probably replace the electrolytics in due course just as a precaution given I know it's such a common problem with Toshiba machines only a couple of years older than this.

Thankfully with the system reassembled it still worked! No particular reason it shouldn't have done, but it's always a little nerve wracking taking apart a portable computer which wasn't *really* designed with service in mind.

Elsewhere in my collection I have an IBM ThinkPad 755Cs, which dates from almost exactly the same time period as this and would have been an obvious competitor. One big difference between the two is that the IBM only has a DSTN display panel rather than the TFT of the Toshiba. This will be quite useful for me though as it will allow me to provide more of a direct comparison between the two when I have a chance to get them set up side by side.

Aside from the failure of the floppy drive spindle drive belt, the only area where the system really shows signs of its age is with the display. Particularly when viewed from oblique angles you can clearly see that there's a loss of contrast towards the bottom of the screen. This seems to be something which is quite common with TFT displays of this sort of age (I believe it's down to the external polariser separating from the display). While it's a little unsightly though it doesn't at least in this case affect usability at all.

Add a bigger display and a touch pad and you've basically got the framework there of a modern laptop.

This page last updated:

28th April 2023: Revised Statcounter code to allow for HTTPS operation.

16th March 2023. Added link to system documentation page.

15th March 2023. Initial page created and uploaded.